Does anyone else remember this game? And, by "remember," I mean remember its advertisements from Dragon magazine?

Monday, April 22, 2024

Witch Hunt

What is Roleplaying? (Part II)

During the Grognardia drinking game, I suspect my readers have thrown back a few whenever the 1977 Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set edited by J. Eric Holmes is mentioned. Because it was my introduction to the hobby, I still have a special affection for it over all the other D&D products I've bought over the years. Looking back on it now, one of the more notable things about its rulebook is that it doesn't include an explicit section in which Holmes explains the nature of a roleplaying game. In fact, the word "roleplaying" (or "role playing") only appears in its text three times, one of them being on the title page.

To some extent, this is understandable, since the Holmes rulebook hews very closely to the text of the original 1974 little brown books, where the word "roleplaying" does not (I think) appear at all. Aside from the aforementioned title page, the two other places where the word appears are the preface (by an unknown author) and the introduction (presumably by Holmes). Here's the relevant section of the preface:

Friday, April 19, 2024

Small is Beautiful

Once I became a player of Dungeons & Dragons, I naturally gravitated toward paying even closer attention to maps of the Middle Ages. What I noticed is that, during many periods of medieval history, many parts of Europe were divided into a crazy quilt of petty kingdoms and principalities. This isn't news to anyone with even a little knowledge of history, but it was positively revelatory to me at the age of ten. Growing up in a world of superpowers and large nation-states, this was contrary to my own sense of what the world was like or indeed could be.

In recent years, I've found myself thinking more about those maps of the Middle Ages, especially as I further develop the setting of Secrets of sha-Arthan. For example, the Empire of Inba Iro is actually made up of twenty districts, each of which is ruled by its own king, who, in turns, swears fealty to the King-Emperor of da-Imer. I've taken one of these districts, the Eshkom District, and fleshed it out for use as the starting area for new campaigns. The district is actually quite small – about 60 miles east to west and 45 miles north to south – because I think that's more than large enough to contain more than enough opportunities for adventure without overwhelming a referee new to the setting.

Over the years, I've drawn a lot of setting maps and I've fallen prey to the urge to "go big." I suppose that comes from having looked with awe at the maps of Middle-earth one too many times as a kid. There's something undeniably appealing about a huge map covered in evocative and mysterious names. Such maps seem ripe with possibilities. However, as I've gotten older, I've come to feel that, lovely though they are to look at, big maps rarely get used to their full potential. More often than not, they wind up being akin to those world maps in the Indiana Jones movies, marking only a handful of places the characters pass through on their way to the site of their next adventure.

Nowadays, I'd much rather the characters spend more time in a smaller area, getting to know it better than they ever could if they were constantly flitting about from one end of a big map to the other. My Twilight: 2000 campaign, for example, has spent the last two and a half years of play within a fairly small part of Poland. Likewise, the Traveller campaign in which I'm playing has taken place entirely within a couple of subsectors in the Crucis Margin sector. This has helped to give it a "cozy" feel that I've come to enjoy. Rather than simply being a huge swath of Charted Space comprised of hundreds of planets, each one indistinguishable from the last, Crucis Margin feels like a distinct place, with its own unique feel. I think that can be important to the success of a campaign.

What's your experience with smaller campaign areas? Do you like them? How do they compare to larger areas in terms of contributing to player attachment to a setting? I'm quite curious about this, because, looking at the RPG settings that have been sold over the years, most of them seem to lean more toward the large and I wonder whether this has influenced the preferences of gamers. Let me know what you think.

Thursday, April 18, 2024

At Arm's Length

I've sometimes been asked about how I handle such things in my campaigns, particularly those in House of Worms. Even before the recent unpleasantness, Tékumel long had a reputation – somewhat undeserved in my opinion – for being a particularly brutal setting that included lots of aspects of pre-modern societies that, while perhaps "realistic," are usually glossed over, if not outright excluded from games like Dungeons & Dragons. The same, too, could be said of almost every RPGs whose setting is a time of war or strife, whether that setting be pre-modern, modern, or futuristic. How does one referee a campaign that contains such dark elements?

As with most aspects of my refereeing, I don't have any systematic answers, only anecdotes and examples. However, looking back over what I have done does, I think, provide something approximating an overarching philosophy that might be of use to others referees whose campaigns deal with such things. For example, let's look at a ubiquitous and indeed foundational aspect of most of the cultures of Tékumel: slavery. Abhorrent though it is, slavery is commonplace throughout history. Indeed, there's scarcely a human society that hasn't practiced slavery at one time or another. Though a fantasy setting, Tékumel draws on several real-world cultures for inspiration, like ancient Egypt, the Aztecs, and Mughal India, all of which practiced slavery, hence its inclusion in Empire of the Petal Throne.

The player characters of the House of Worms campaign are thus all members of a slaveholding culture and do not question the practice. Their clan owns slaves and at least a couple of PCs have had personal slaves who became important NPCs (though one was later manumitted and adopted into the clan). Despite this, slavery has never been important part of the campaign. It's part of the "furniture" of the setting, something that's undeniable there, but that we've never really dwelt upon, because the focus of the campaign has always been on adventure, usually out in the wilds, far from any Tekumeláni civilization.

Similarly, the major cultures of Tékumel all approve of human sacrifice to varying degrees, as have many cultures on Earth. The god most of the characters worship, Sárku, accepts such sacrifices as part of his rituals and so priestly characters have occasionally been involved in them, too. The same is true of the torture of prisoners, which is seen as a legitimate form of interrogation in Tsolyánu and elsewhere. So, again, these deeply repugnant elements of the setting have appeared from time to time, but they've never been its focus. When they have appeared, such as during attempts to invoke divine intervention (for which there are rules), we'd simply acknowledge it and move on – the equivalent perhaps of the cinematic "fade to black" of old.

I could cite plenty more examples from both House of Worms and Barrett's Raiders, but I trust that's not necessary. What I have come to realize is that, unless it's absolutely relevant, I don't spend a lot of time going over the finer details of all the unpleasant things that happen in my games. This includes combat, by the way, which, as players of many old school RPGs know, is generally very abstract. Now, there are indeed times when the precise nature of a horrible injury is relevant – this has come up several times in the Twilight: 2000 campaign – and, in such cases, I don't shy away from the gory details. However, as a general practice, I avoid doing so, because my games are meant to fun escapes rather than luxuriating in the darker corners of the human soul.

I offer my experiences not as a universal prescription. Each referee and player will draw his lines in different places and that's as it should be. I personally feel that there's generally nothing wrong with including unpleasant realities in one's roleplaying so long as everyone's on the same page in this regard. I don't fault anyone who wants to keep his games "family friendly," but neither do I condemn anyone who wants to venture farther into the shadows. One of the things that's great about roleplaying is that it's a flexible enough entertainment that it can accommodate both approaches – and more besides – without any difficulty.

Wednesday, April 17, 2024

Retrospective: Cyberpunk

I'm fairly certain that 1988's Cyberpunk, published by R. Talsorian Games, included a short bibliography of cyberpunk books that I would eventually find useful in much the same way as Appendix N had been for fantasy. Though I'd been a huge SF fan since I was quite young, most of my favorite stories and authors dealt with space travel, aliens, and galactic empires rather than more earthbound topics. Consequently, I didn't take any notice of William Gibson's influential 1984 novel, Neuromancer, or any of the other seminal works by him and others that both followed and preceded it.

Truthfully, I probably wouldn't have noticed Cyberpunk either when it was first released. I was away at college at the time and, while there, I became friends with a student a year older than I, who was much more plugged into the current trends of SF. He was also, as it turned out, a big fan of the 1982 movie, Blade Runner, his dorm room down the hall regularly blaring its Vangelis soundtrack at odd hours. It was through him that I was introduced not just to cyberpunk literature but also to Cyberpunk "the roleplaying game of the dark future." He refereed several adventures for myself and our mutual friends that never quite amounted to a proper campaign. but we had fun and they succeeded in increasing my interest in and appreciation for cyberpunk SF.

Cyberpunk came in a black box that featured an illustration that reminded me somewhat of Patrick Nagel, whose distinctive line art will indelibly be linked in my memories with the 1980s. For that matter, cyberpunk – the literary genre, the esthetics, and the RPG – is, for me, a quintessentially '80s phenomenon, despite the fact that it's supposedly about the future. That's not a knock against it by any means. In my estimation, nearly every work of science fiction is really about the time in which it was created, but cyberpunk, with its mirrorshades, megacorps, and rockerboys (not to mention its American declinism and Japanese fetishism) somehow feels every bit as dated as the atomic age optimism of the 1950s. Though I regularly joke with my friends that we currently live in the worst cyberpunk setting ever, the world envisioned by Cyberpunk is now solidly within the camp of a retrofuture.

I say again: this is no knock against Cyberpunk. At the time I was introduced to it, at the tail end of the Cold War and the dawn of the Internet Age, it felt incredibly bold, fresh, and relevant. Plus, I was nineteen at the time and, even for congenital sticks in the mud like me, the lust for rebellion is strong. That, I think, is a big part of why Cyberpunk succeeded so well in establishing itself: Mike Pondsmith and his fellow writers had succeeded in making rebellion – or a consumer-friendly facsimile of it – the basis for a game that also included trench coats, neon signs, chrome-plated prosthetics, and guns – lots of guns. Say what you will about its plausibility or realism, but it was a brilliant stew of elements that somehow worked, despite the objective ridiculousness of it all.

Inside that black box were three booklets, each dedicated to a different aspect of the game. "View from the Edge" contained the rules for creating a character, including its "roles" (i.e. character classes) and life path system. As a fan of Traveller's character generation system, I really appreciated the latter, since it helped bring a new Cyberpunk character to life. "Friday Night Firefight" was devoted entirely to combat and to weapons. As I said, this was one of the big draws of the game, at least in the circles in which I traveled at the time. Finally, "Welcome to Night City" presents an urban locale that I took to be a stand-in for any dystopian megalopolis, though, as I understand it, was eventually established to be an actual city within R. Talsorian's official Cyberpunk setting.

More than thirty-five years after its original release, it's difficult to overstate just how new this game felt upon my discovery of it. Some of that is, as I've suggested, due to my own limited tastes in science fiction up till this point, which made Cyberpunk feel even more revolutionary than is probably warranted. Still, there is something genuinely brash about the game, both in terms of its subject matter and its presentation. The artwork, for example, is frequently dark, moody, and violent, which set it apart from the increasing stodginess of, say, Dungeons & Dragons and perhaps even laid the groundwork for the coming tsunami of White Wolf's World of Darkness.

Like a lot of games, I'm not sure I could ever play Cyberpunk again, though, in fairness, I'm not sure I could ever play any game in this genre anymore, since the real world is now frequently more unbelievable than anything a SF writer could dream up. At the same time, I retain an affection for this game, which served as my introduction to the genre. Further, I recently learned, completely by accident, that the older student who lived down the hall from me died almost a decade ago. We'd lost touch over the years and, while I'd occasionally think of him, I never made the effort to try and reconnect. Now, it's too late – but I still have many fond memories of late nights holding off security goons while our netrunner tried to break into a corporate data fortress.

Rest in peace, Chris, and thanks for the good times.

Tuesday, April 16, 2024

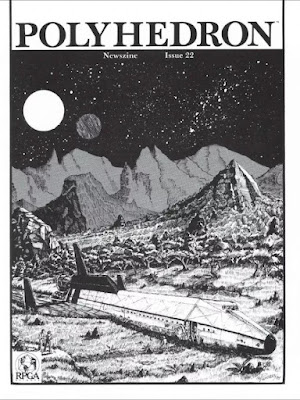

Polyhedron: Issue #22

Penny Petticord's "News from HQ" has two items worthy of note. The first is an announcement that Polyhedron is actively seeking submissions from readers. Petticord states that "only a few members" have thus far been making submissions and she'd like to change that. I wish I'd paid more attention to this at the time, because I made several submissions to Dragon while I was in high school and all were rejected. I might have had a better shot with Polyhedron, given the dearth of submissions. Secondly, Petticord warns readers that the next issue will a "special April Fool" issue, so "don't believe anything you read" in its pages. Fair enough!

This issue also features a large letters page, with multiple letters written in response to Roger E. Moore's "Women in Role Playing" essay from issue #20, While not all of the letters were critical, many of them were, largely because the readers felt that Moore had "belittled" or otherwise failed to understand female gamers. Though Moore apologizes for any unintended offense, he nevertheless stands by what he wrote, noting that it's an important topic in need of more frank discussion. Some things never change, I guess.

Gary Gygax returns to this issue, writing yet again about marlgoyles and their reproduction. He provides AD&D stats for every stage of the creature's growth from hatchling to mature. It's baffling to me, but it's definitely in keeping the naturalism that's a hallmark of his worldbuilding. He also provides stats for a "monster" that was somehow left out of Monster Manual II – amazons. Amazons, in Gygax's vision, are a female-dominated society of barbarians, with menfolk in secondary or support roles. Beyond that, he doesn't have much more to say about them, which I found a little disappointing, because they're a great fantasy concept worthy of inclusion in D&D.

Frank Mentzer's "Spelling Bee" focuses on druid spells and abilities. Interestingly, Mentzer concern this time seems more focused on reining in druid abilities (like shapechange) that he thinks can be easily abused rather than on finding new and creative ways to make use of them. "The RPGA Network Tournament Ranking System" article is not especially interesting in itself, at least to me. However, the accompanying ranked list of RPGA judges and players is. Gary Gygax, for example, is the only Level 10 Judge, just as Frank Mentzer is the only Level 9. There are no Level 8 or 7 Judges and only one Level 6 (Bob Blake). The names on both lists include quite a number of people who either were at the time or would later be associated with TSR or the wider RPG world. It's a fascinating window on a particular time in both the hobby and the industry.

"In the Black Hours" is an AD&D adventure for levels 6–9 by David Cook. The scenario is unusual in a couple of ways, starting with its lengthy backstory about a high-level mage who learned the true name of the demon lord Juiblex and, in order to protect himself, was eventually forced to imprison the demon with a magical crown. That crown has now come into the possession of a merchant who wishes to protect it from would-be thieves (employed by Juiblex's demonic underlings who wish to free him). The characters are hired by the crown's present owner to protect it over the course of the night when he believes the thieves will make their attempt. There's a lot going on here and the basic structure of the adventure – mounting a defense against waves of attackers – seems well suited to a tournament set-up. If anyone ever played this scenario (or one like it), I'd be very curious to hear how it went.

"Away with Words" by Frank Mentzer is a 26-word multiple choice quiz that challenges the reader's knowledge of High Gygaxian words. It's a fun enough little diversion, though less hard now, thanks to the ubiquity of online dictionaries. "Unofficial New Spells for Clerics" by Jon Pickens does exactly what it says: offers a dozen new spells for use by clerics. Most of these spells are connected in some way to existing magic items, like the staff of striking or necklace of adaptation, filling in gaps in the spell list that, logically, should exist. While that certainly makes sense, it's also boring and exactly the kind of magic-as-technology approach that I've come to feel kills any sense of wonder in a fantasy setting.

"Dispel Confusion" continues to narrow its scope. This issue we're treated only to questions pertaining to D&D, AD&D, and Star Frontiers. Most of them are the usual collection of nitpicks and niggling details. However, one stood out as noteworthy (and indeed unexpected):

Monday, April 15, 2024

"Gimme a break!"

By the time the Dungeons & Dragons cartoon series premiered in September 1983, I'd been playing D&D almost four years. I was also just shy of fourteen years old. Perhaps inevitably, I greeted the arrival of the cartoon with some trepidation, despite the involvement of Gary Gygax as its co-producer. That's because, at the time, I was increasingly concerned about the "kiddification" of my beloved D&D. Consequently, I turned up my nose at the cartoon and only caught a handful of its 27 episodes when they were originally broadcast.

Fantasy Master: Michael Moorcock

REVIEW: A Folklore Bestiary (Volume 1)

Thursday, April 11, 2024

The True Birth of Roleplaying

Though I was not an avid reader of comic books when I was a kid, I did read them – mostly Star Wars, Micronauts, and the occasional Doctor Strange issue. Nearly as much as the comics themselves, I loved looking at the advertisements. I could (and probably should) write several posts about all the weird and wonderful stuff that was being hawked on the pages of comics in the 1970s, but the one that, to this day, still sticks in my brain, is the one to the right, offering 100 toy soldiers for a mere $1.75.

Though I was not an avid reader of comic books when I was a kid, I did read them – mostly Star Wars, Micronauts, and the occasional Doctor Strange issue. Nearly as much as the comics themselves, I loved looking at the advertisements. I could (and probably should) write several posts about all the weird and wonderful stuff that was being hawked on the pages of comics in the 1970s, but the one that, to this day, still sticks in my brain, is the one to the right, offering 100 toy soldiers for a mere $1.75.

I never took the plunge and bought this. As alluring as it was, I had the sneaking suspicion that it was too good to be true. Plus, I already owned a very large number of toy soldiers – or "army men," as my friends and I typically called them – so there was no immediate need for more of them. My soldiers were all molded from camo green plastic and, from the look of them, were modeled on World War II era US troops. There came in a dozen or so different poses, including a medic, a sniper, a mine detector, and one aiming a bazooka. One of my friends had a collection of German soldiers molded in gray plastic, along with the Navarone play set that we all envied.

One of the main ways my friends and I would play with our army men was by finding a large, open space, whether outside or inside, and then arranging our toy soldiers in various positions. Many of them we'd place right out in the open, but some of them we'd secure behind "protection" of one sort or another, such as rocks, potted plants, or even other toys, like appropriately scaled military vehicles (jeeps, tanks, etc.). After we'd done this, we'd then take turns shooting rubber bands at one another's battle lines, with the goal of "killing," which is to say, knocking over as many of one another's soldiers as possible. We'd keep doing this until only one person had any army men still standing. He'd then be declared the winner of this "battle." Sometimes, we'd have longer "wars," consisting of multiple rounds of battles, the winner being determined by which army won the most battles.

This was simple, childish entertainment, but we had a lot of fun doing it. I can't quite recall when we first started using our army men in this way. We were probably fairly young, because I cannot remember using them any other way. Consequently, the rules of rubber band warfare slowly evolved over the years, as a result of adjudicating disputes and edge cases, such as what constituted being "killed" for soldiers, like the sniper, who was already lying horizontally or indeed just how horizontal a soldier had to be in order to qualify as "dead." In my experience, both as a former child and as a parent, these kinds of negotiated "house rules" are quite common, a natural outgrowth of the fact that no set of rules, no matter how extensive, is ever going to cover every circumstance. Kids intuitively understand this and act accordingly.

Another natural evolution was identifying with and even naming particular army men who'd survived multiple rubber band attacks and somehow, against the odds, continued to stand. I recall one soldier, who had a Tommy Gun and a grenade, who, for a time, seemed unbeatable. A combination of good luck and good positioning made him seemingly invincible. He belonged to a friend's army and, after the friend had one the battle in which the soldier had participated, he acquired a name: Sergeant Phil Garner, named after the mustachioed second basemen of the Oakland Athletics – don't ask me why. Sgt. Garner set a precedent and soon we were all naming and creating stories about the army men who survived or otherwise distinguished themselves in our rubber band wars.

I've always found it interesting that, when trying to describe roleplaying to those unfamiliar with the hobby, game designers will often analogize it with Cops and Robbers or improvisational theater – not because the analogies are necessarily wrong but because RPGs, as we know them today, grew out of miniatures wargaming. It's not for nothing that OD&D's subtitle is "Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures." Though I was never, strictly speaking a wargamer of any variety, I cannot help but think that my early experiences fighting wars with army men and rubber bands served as an unintentionally excellent propaedeutic for roleplaying. I doubt my friends and I were unique in this regard.

|

| Thank you for your service. |